By “The Russian” Nikolai Razouvaev

Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the greatest of them all? People often compare great athletes from different eras; what if Bernard Hinault raced against Eddy Merckx? How would that go? Or how would Wayne Gretzky compare to Valeri Kharlamov if both played in the NHL? Or how about Bobby Fisher v Garry Kasparov? (by the way, here’s a good piece by Kasparov about “How the king of chess lost his crown“).

At any rate, this is not a what if post; I’m not going to bore you with speculations about what could have happened if … I have an opposite goal in mind – I’ll try to argue why comparing contemporary athletes separated by political barriers is a fruitless exercise.

This post was “inspired” by Lucio, a Facebook friend from Lombardia who asked me if, in my opinion, Sergei Soukhoruchenkov would have won Tour de France or Giro d’Italia had he turned pro at 23 instead of 33 when his career was pretty much finished.

Some Background

I realise there’s not a great deal of information available about Soukhoruchenkov (known as Soukho in the West), so I’ll briefly outline who he was as a cyclist.

I watched my first Course de la Paix (Peace Race for plebs) in 1979, the year Soukhoruchenkov won it the first time. I was 13, he was 23. If there was a sport hero for me at the time, he was it. I don’t remember how exactly he won it, all I remember was one long, crazy solo attack he did some time during the race, got the yellow jersey and never let go of it.

Next year we had Olympic Games in Moscow and as you probably know, it was boycotted by the United States. The rest of the Western world boycotted it too but allowed their athletes to go to Moscow on their own. I don’t know how the boycott affected other sports. In my opinion, it had little impact on cycling – the main players were all there including some from Western countries such as the then current World Road Champion Gianni Giacomini, the 1978 World Road Champion Gilbert Glaus and of course all the heavy hitters from GDR, Poland and Czechoslovakia. My friend and I watched the live broadcast at my sister’s because she owned a colour TV (we didn’t).

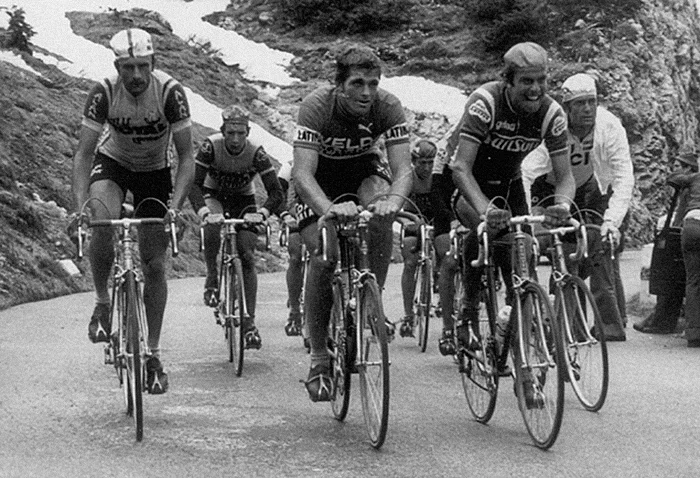

I remember the race pretty well. The Krylatskoye circuit was specifically built for this race and was absolutely insane. I raced on it 5 years later and left some skin and buckets of sweat on those roads. It’s one crazy circuit with banked corners and walls to climb. Anyway, the break went very early with Barinov, Lang and an Italian guy who crashed soon after. Soukhoruchenkov bridged to the break and they were gone, two Russians and a Pole. With about 50 km to go, Soukhoruchenkov attacked and soloed to the line. Textbook win.

Everyone expected him to win Course de la Paix again in 1981 after the Games but he didn’t – he finished 2nd while Shakhid Zagretdinov, his team-mate, won. This is when things went south for him – he didn’t make the team for 1982 Course de la Paix, went off the radar in 1983 and then somewhat miraculously re-emerged in 1984 to win Course de la Paix again.

These are just some highlights of his career. The UCI recognised him as the best cyclist in the world in 1979, 1980 and 1981 (professional cycling was not governed by the UCI back then, imagine that).

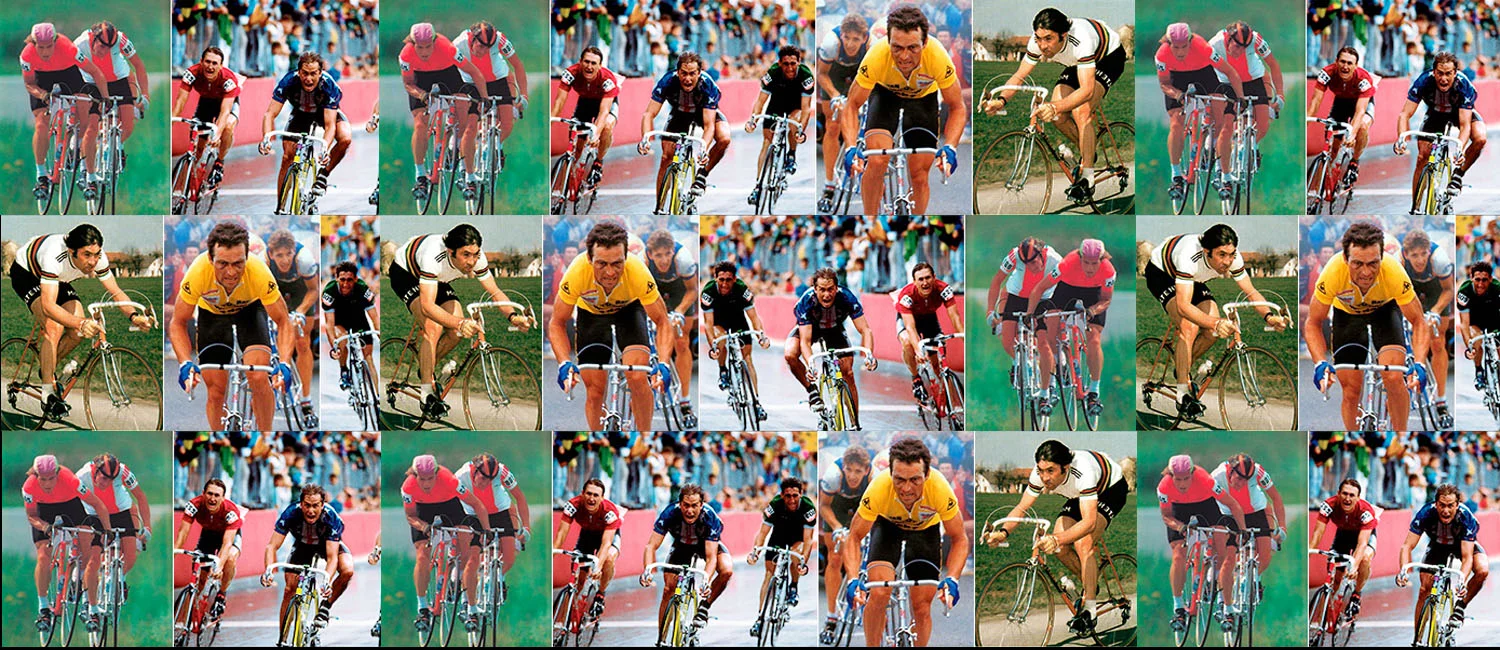

He was often compared to Bernard Hinault – tough, never give up attitude, not a pure climber but impossible to get rid of even on steep climbs if he’s determined to stay. And because of that, a lot of people wondered – what if ..?

No ifs and no buts

Now, even though it’s clear Soukhoruchenkov was made from the same kind of dough as Fausto Coppi, Gino Bartali, Eddy Merckx, Bernard Hinault, Greg Lemond that a few others were made from, there’s really no way of knowing how things would have unfolded for him in professional cycling because:

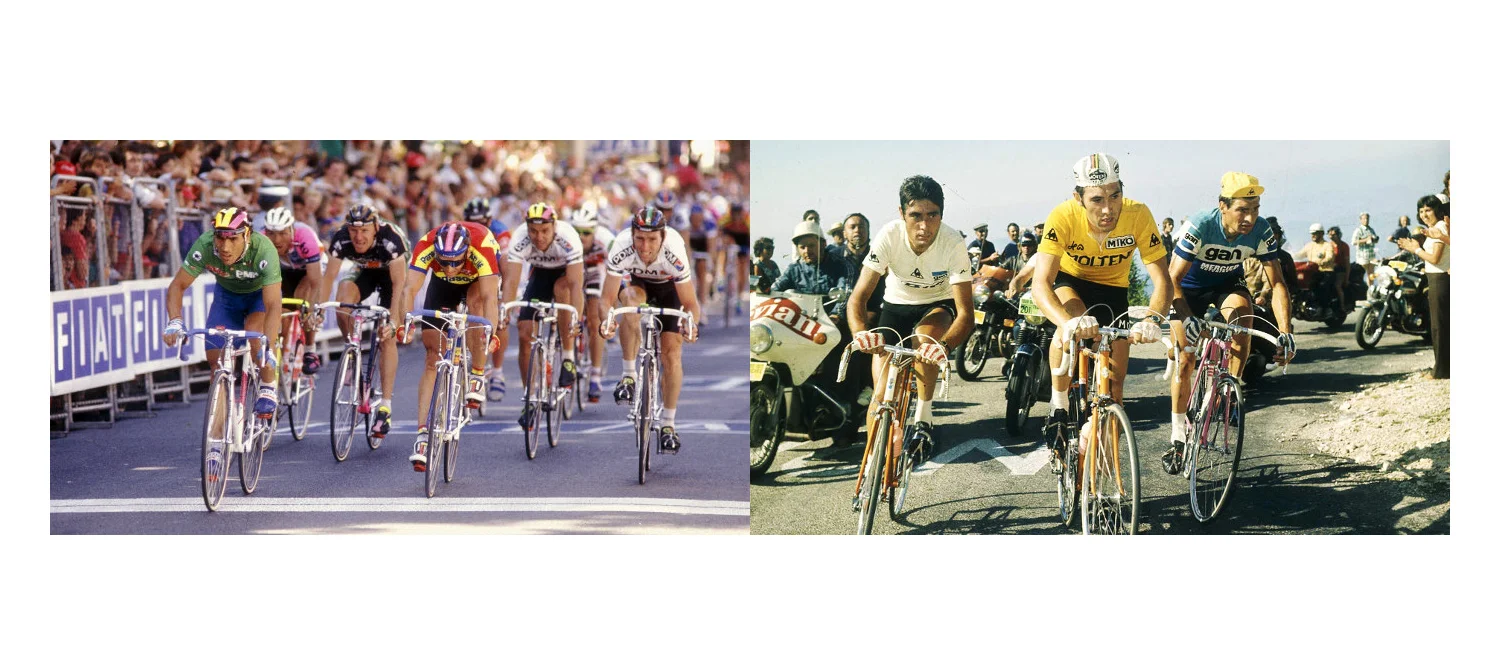

(1) Amateur cycling, as tough as it was, never had anything even close to a professional racing calendar. For example, Course de la Paix aside, there was nothing even resembling a Grand Tour. Course de la Paix itself, without taking anything from it as a mother of all amateur stage racing, lacked the Alps, the Pyrenees, and the one hour long hors catégorie climbs. True enough, there are some hard climbs in Tatra Mountains but there wouldn’t be 5-6 high mountain stages in a single race. It wasn’t an easy race, but you can’t really compare the Tour or the Giro with the Course de la Paix.

There were no Classics either. This is because about 90% of amateur racing was domestic. Each country had its own domestic calendar which is where most of the racing was happening. This, in turn, meant that international amateur calendar was pretty thin and it was thin because only national teams and well funded clubs could afford to travel to international races. A thin international calendar leads me to my next point:

(2) With only World Championships and Course de la Paix as the major battle ground between amateurs, it was hard to know where the best riders stood on the international arena. Apart from these two and a couple of other bigger races (e.g. Tour de l’Avenir, Milk Race or Giro delle Regioni), the peloton’s make up at other international races was a bit anarchic; a mixture of 2-3 top national teams racing against local teams in whatever country the race was in. You might think that you rock the world while racing somewhere in the south of France and then you meet an A-team from GDR a month later somewhere in Holland and they remind you of your place in the hierarchy very quick. Had these meeting been ongoing against more or less same opposition as it is often the case in professional cycling, the fans and the racers would have known where most people stood; a clearer picture of who is who in amateur cycling would have been available for all to see.

Speaking of racing against inferior opposition, here is my next point of why comparing amateur stars with professional stars is nonsensical:

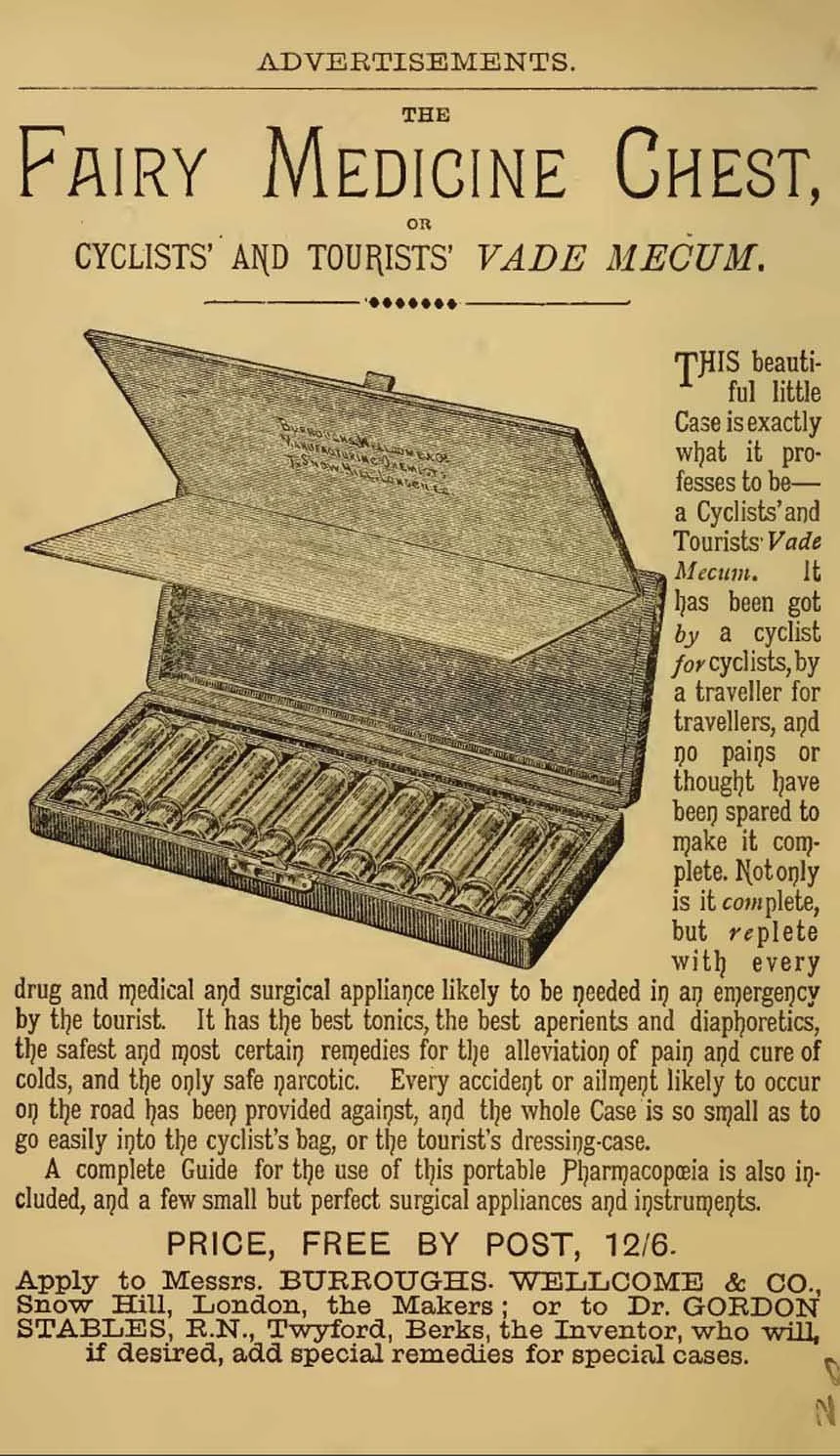

(3) Eastern Bloc amateurs were not amateurs in any meaningful sense of this word – they were professionals. Not only they were well paid to race their bikes, they also had all the time in the world to train and prepare for racing while most Italian, Dutch, Belgian, French etc amateurs had no such luxury – they had real jobs to do at home. Again, it doesn’t mean winning Tour de l’Avenir was easy, it wasn’t, but it does place Eastern Bloc domination of amateur cycling in a proper perspective when these things are considered. And finally, the race dynamics:

(4) The Soviets were the only riders in the world who valued stage races' team classification more than individual. Not a well known fact, I reckon, but still a fact. The socialist ideology, peppered with communism, elevated collective effort over individual (never mind that collective is only a sum total of individual). Applied to road cycling, it meant that the Kremlin chiefs required the national team to chase team classification first with individual one being an icing on the cake. If you can do both, great, but don’t you dare to lose team classification to GDR.

If you look at the statistics, you’ll see the Soviets won Course de la Paix in team classification 20 times while the 2nd best team, GDR, “only” 10. The individual classification is 12-10 in GDR’s favour.

This approach led to some awkward tactics on the road with everyone puzzled about what the Russians were up to. For example, a typical situation might have been where the Soviets would shut down a break because it was hurting their team classification even though the break favoured their individual standings. Except the Russians, no one else knew what was going on.

This, by the way, partially explains why the Soviets were hopeless in major one day races like World Championships (only 2 gold medals in the entire history ofUSSR) – they were not used to race without team classification as their priority. This deficiency and inability to race for yourself was revealed later when the Soviets were finally allowed to race as professionals from 1989 and only a handful of riders who were naturally more aggressive than others and hungry for individual success, such as Tchmil or Konyshev, made it to the top of professional cycling.

As for Sergei Soukhoruchenkov, when he signed a contract with Alfa Lum as part of the first wave of Soviet riders to go pro, he was 33, way past his best years and nowhere near the level he needed to be at to race against the likes of Lemond or Indurain at the time.

Shimano vs Campagnolo in the 80's & the beginning of Carrera Bicycles